The door to Josefina Rivera’s motel room sits wide open, sending music clear across the parking lot.

The door to Josefina Rivera’s motel room sits wide open, sending music clear across the parking lot.

The room snugly holds a dorm-sized refrigerator, a microwave oven and a dinner table with enough space for two small settings. The television is bolted to the wall, closer to the ceiling than the floor. In the bathroom, the new bride’s wedding dress hangs from the shower rod.

Josefina Rivera’s whole life has been governed by confinement. But unlike her past digs, this cramped roadside motor lodge near Atlantic City is no claustrophobic way station–it’s her home. Rivera says she’s happier here than she’s been in years; happier than she was roaming the streets of North Philadelphia after fleeing a foster home at 12; and far happier than she was when she was living in Girard Avenue flop-houses, turning tricks and shooting cocaine.

Sitting on the double bed that monopolizes the space she calls her own, Rivera is about to replay the story of her lifelong nightmare.

It is the first time she has chosen to share her story at length in 15 years. (Rivera did grant one television interview regarding Heidnik’s sanity around the time of his execution).

Having previously announced she’d only tell her story for money–a request she did not make during a recent series of interviews for PW–Rivera now hopes her account will help those who may be making the kind of mistakes that nearly ended her life.

“My story could benefit a lot of girls, the ones that only see one side of prostitution,” she says. “They think they can run outside, make some money and then–boom–they’re on their way. They don’t think anything can go wrong. Well, guess what? Something can go wrong.”

Leaning forward to be heard over the music videos playing on the television, the petite 41-year-old says it all turned out better than could be expected.

Grabbing the remote, she lowers the decibels on P. Diddy.

“I still have problems with my hearing,” she apologizes. “Can’t even hear myself talk sometimes because of what he did with the screwdrivers. It’s just one of those things I still have with me. One of those things I’ll always have with me.”

Rivera looks out the door to her motel room just as an F-16 fighter jet from a nearby air station roars out to sea. As it trails off into the sky, she starts to talk about the night that changed her life.

The night a $20 hour of sex became four months of life-shattering hell.

The night she met Gary Heidnik.

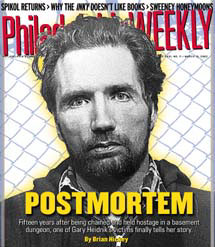

Fifteen years ago this month “House of Horrors” became the trademark designation for what may be the most gruesome crime in Philadelphia history.

On March 25, 1987, a hysterical prostitute called the police, ranting about how she’d just escaped a madman who’d held her and five other women hostage inside his N. Marshall Street rowhouse, near Broad and Allegheny.

At that moment three women were still chained to Gary Heidnik’s basement pipes, naked but for their shirts. Body parts from another victim were stored in his refrigerator. Two days earlier, he had dumped a woman’s electrocuted corpse in the Pine Barrens.

The woman showed the police the scars on her ankles from the muffler clamps Heidnik had used to tether her to sewer pipes in the dirt-encrusted basement. Responding to her claims of brutality, police drove to the nearby gas station where she said Heidnik would be waiting for her to show up with another victim. It was the promise she made to hatch her escape.

At the gas station police found Heidnik sitting in his Cadillac Coupe DeVille. When they went to his house and knocked down the front door, they faced a horrifying crime scene.

By the time police returned to take a morbid inventory, the city’s newsrooms were going into overdrive. Officials were at a loss to explain what they were learning. But not Rivera, who was inside the Roundhouse giving a 27-page statement.

Her story began a couple nights before Thanksgiving 1986, when Heidnik picked her up at Third and Girard and drove her back to his house to have sex. She says it was the first time she’d gone to someone’s house rather than diverting them to an alley or a parking lot. She figured she’d leave when they were done, but Heidnik–a 43-year-old high school dropout and self-ordained minister who had a knack for making money in the stock market and a history of sexual abuse and mental problems–had other plans: He grabbed Rivera by the neck and choked her into unconsciousness.

She woke up handcuffed to his bed. Later Heidnik led Rivera down into his basement and shoved her into a hole he’d dug in the floor. He placed a board over the pit and secured it with dirt-filled trash bags. Josefina Rivera had become the first of his helplessly trapped victims.

She would not be alone for long.

Within a couple weeks Heidnik had lured 24-year-old Sandra Lindsay, a mentally retarded friend, into his house and imprisoned her in the same sadistic fashion. Around Christmas 19-year-old Lisa Thomas became hostage number three, followed shortly thereafter by 23-year-old Deborah Dudley and 18-year-old Jacqueline Askins. The last victim, 24-year-old Agnes Adams, arrived just days before Heidnik’s arrest.

Each of Heidnik’s victims entered his house unaware of those who preceded her. But each soon knew the hell the others had faced in the basement torture chamber where they were underfed, beaten, sexually brutalized and forced to sleep on soiled mattresses with their arms chained to sewer pipes.

Rivera’s story continues with tales of Heidnik forcing the women to have sex with him, sometimes in front of the others. He was intent on realizing his dream of siring 10 children.

Despite blaring a radio 24/7, Heidnik worried that his victims might call for help when he left the house. To make sure they couldn’t contact the outside world, Heidnik jammed screwdrivers into their ears until he saw blood, leaving his victims with the permanent damage Rivera says still plagues her today.

But that, says Rivera, was hardly the worst of it.

When one of his victims began to choke on the bread that Heidnik force-fed her, he dragged her limp body upstairs. The other victims soon heard an electric saw and “smelled a terrible smell.” They detected the same smell in the food he brought them for their next meal.

A month later, when another victim wouldn’t cooperate with Heidnik, he stuck her in the ditch–the original hole had by now been expanded to sleep three–filled it with water and forced Rivera to hold an exposed electrical wire to the victim’s chains until she died.

Though this is the first time Josefina Rivera, today newly married and working as a waitress at the shore, has chosen to publicly share her story in 15 years, she concedes she’s had to deal with the public about her past more times than she cares to count.

There have been days, lots of them, when facing the Heidnik demon hasn’t been easy for Rivera, whose three children and two stepchildren from her recent marriage all now live in New Jersey.

Rivera’s life since walking away from the courtroom after her testimony against Heidnik has had no big happy ending. She tells of how the victims–herself included–were taunted after the trial by people hollering “Alpo” at them (a reference to the dog food they were forced to eat) and how they were classified as “Heidnik girls” for years afterward.

Rivera says she left the courtroom in 1988–her testimony was critical to the prosecution and helped earn Heidnik the death penalty–with no place to live and not even anything to wear until the District Attorney’s Office came through with a clothing allowance. The victims each received roughly $30,000 in a settlement with Heidnik’s estate–he had turned $35,000 in investments into nearly $600,000–but the money didn’t go far.

“In the beginning,” recalls Rivera, “there was talk about putting us in mental hospitals or medicating us with antidepressants to help us deal with everything,” she recalls. “They didn’t know what to do. They never asked what they could do to help us get over it. We were guinea pigs, really.”

Rivera says everybody she ran into immediately afterward wanted to hear her story, and for a while she told it over and over again. “[But] I just wouldn’t do it,” she says of the suggestions she received to get therapy. “I knew I wasn’t the crazy one. I wasn’t the person who locked women in my basement. I never went to any of that and I still haven’t. I don’t know if that’s good or bad really. I just accepted a lot of things when I was down in that basement.”

Instead of seeking treatment, Rivera began to self-medicate. Like several of the other survivors, she fell back into a dangerous lifestyle. She does say, though, she never considered suicide or gave up hope.

“It didn’t scare us straight,” she says. “A lot of us went back up to Front Street [an open-air drug and prostitution market at the time]. I guess we just figured this is the worst thing that could ever happen to us, so why not go back up there to make money and get more drugs?”

Rocking back and forth with her lion slippers dangling over the edge of the bed, Rivera puffs on a Marlboro 100 and makes direct eye contact with a reporter. She says she reached her breaking point after watching too many people die on the streets of North Philadelphia.

“My friends were dropping like flies,” she says. “I just had to try something different. I had to get the hell out of Philadelphia.”

Her husband Theron listens as Rivera tells her story. He didn’t know of her past when they met five years ago, but one day he says Rivera just sat him down and told him. They’re only now planning to tell his parents about it.

For the past five years the couple has called a series of hotels and motels home. Rivera says she’s happy now living close to her family. The reminders of Heidnik are just an hour up the expressway. Whatever the distance, she says, the past is impossible to avoid. Today the reminders come in the form of hearing problems and aching shoulders from being bound in the basement.

When she sees someone digging a hole, she sees Heidnik. She sees him every time she sees a guy with a beard. When she notices generic food in a supermarket, it reminds her of the hot dogs, bread, rice and other cheap food Heidnik fed them–when he fed them at all. The memories of eating dog food and biscuits are only as far away as the dinners she buys her kitten.

Rivera has read that the serial killer in The Silence of the Lambs was partially based on Heidnik, but she’s never seen the movie.

“Sometimes I’ll just see somebody and think to myself, ‘It’s a nut! It’s a nut!'” she says. “The shrinks told me that I’d never function normally again.”

There are two things Rivera says she’ll never reconcile: The deaths of Heidnik victims Sandra Lindsay and Deborah Dudley.

Lindsay was the first to join her, the helpless one who never stood a chance; Dudley was among the last, the one “who just wouldn’t give in.”

Had Heidnik killed Dudley on his own, it would have been hard enough. But the fact that he ordered Rivera to commit the crime with him makes it all the more haunting. Not only did she electrocute the woman (she believes Heidnik would have killed her had she not obliged), but he forced her to sign a confession before the two drove to New Jersey to dump the body.

“I remember putting the wires on her chains,” she says. “People don’t think that it bothers me, but it really, really does. Her family might not be as understanding. I wanted to go to her funeral but the DA’s Office told me not to. I haven’t spoken to them to this day.”

Rivera says the court pit the survivors against each other, just like Heidnik did with his sadistic mind games.

When the case went to trial, Rivera faced accusations that she was “the boss of the basement.” To some, she was a co-conspirator who, according to Heidnik’s attorney, “fed a sick mind.”

To others she was the “pet captive” whom he afforded the special treatment of sleeping in his bed and even leaving the house with him on occasion. It was alleged she suggested methods of torture, helped inflict punishments and even ratted when the others planned to attack Heidnik. There was even talk of charging her as a conspirator.

In court, victim Jacqueline Askins contended, “They’d [Heidnik and Rivera] come back and tell us how wonderful their day was.”

Fellow victim Agnes Adams bitterly announced how “[Rivera] helped him” when Heidnik attorney Charles Peruto Jr. asked why Rivera never screamed out for help when in a public place.

Fifteen years later Rivera remains true to her story and her plan to save as many of the women as she could when the right time came along. When the chance to get away from him–without drawing suspicion–presented itself, she’d take it. Then she’d call the police so they could nab him before he could return to the house or escape.

Brian Hickey (bhickey@philadelphiaweekly.com) is covering the governor’s race for PW.