“The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.”

—William Faulkner

There is an old saying: Under every mile of railroad track is a dead Irishman. Locally speaking, this is almost literally true.

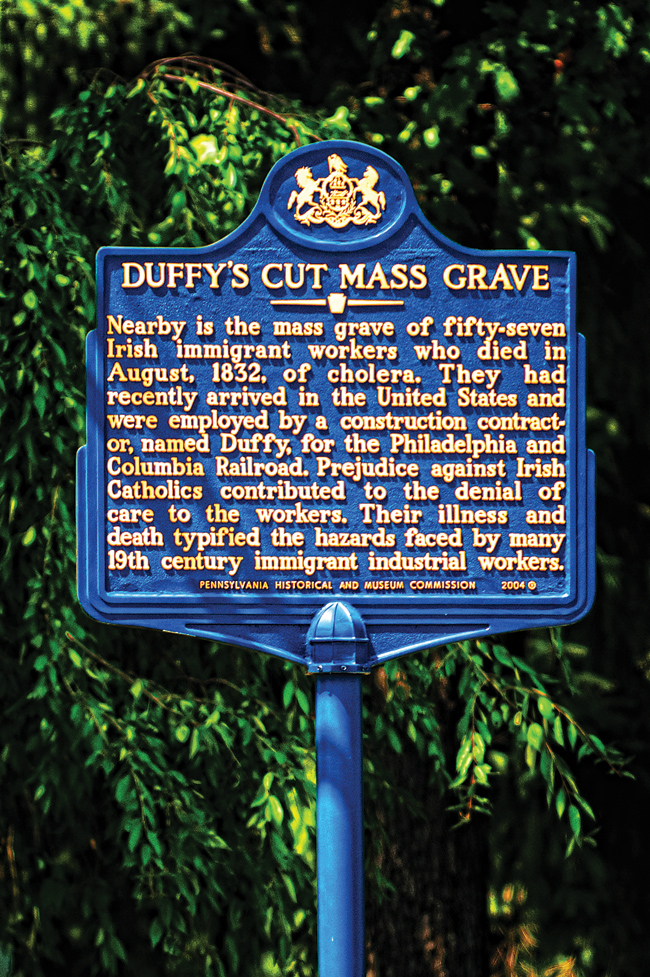

Back in the 19th century, the Main Line, not to mention large stretches of the railroads in this part of the country, were built on the blood, sweat and tears of Irish Catholic immigrants, who back then commanded about as much respect as Mexican immigrant workers command today. Out near Malvern, under mile 59 of what was then the Pennsylvania Railroad and is today SEPTA’s R-5 line, lies the bodies of 57 Irish railroad workers. What killed them remains a mystery—one that, some 178 years later, appears to be on the verge of being solved. The official record says the men died of cholera, but a team of academic researchers known as the Duffy’s Cut Project suspects foul play—that some, if not all, of the men were murdered to stem the spread of a cholera epidemic, then raging in Philadelphia and Chester County. And the researchers may well have discovered the forensic evidence to prove it.

After eight years of digging, the Duffy’s Cut Project has uncovered more than 2,000 artifacts—pipe stems, broken whiskey bottles, forks, buttons, shoe buckles—and four sets of remains. Two weeks ago, they found two more. These were the most complete set of remains yet. Most striking, the skulls had perimortem wounds, meaning caused at the time of death, according to Dr. Janet Monge, a professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania who has been examining the remains. In layman’s terms, the men’s skulls were split open right before they died, just like the two skulls on the skeletons they found the previous summer.

After eight years of digging, the Duffy’s Cut Project has uncovered more than 2,000 artifacts—pipe stems, broken whiskey bottles, forks, buttons, shoe buckles—and four sets of remains. Two weeks ago, they found two more. These were the most complete set of remains yet. Most striking, the skulls had perimortem wounds, meaning caused at the time of death, according to Dr. Janet Monge, a professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania who has been examining the remains. In layman’s terms, the men’s skulls were split open right before they died, just like the two skulls on the skeletons they found the previous summer.

“We know the wounds are perimortem because living bones break differently than dead bones,” says Monge. “At this point, we are not 100 percent certain that this was the cause of death, but when there is more than one set of remains with the same trauma in the same place it is more likely causative.”

In June of 1832, the 57 Irish migrant workers arrived at the docks of Philadelphia. Their job was to lance a flat path for the track through steep, hilly terrain. In railroad parlance, this is known as a ‘cut’ and thereafter that stretch of track would be known as Duffy’s Cut. Six weeks later, they would all be dead. History would blame cholera for their deaths, but history is always written by the winners, and the winners—in this case the railroad company and the landed gentry of Chester County—would be best served by such an explanation. But in fact there is a lot about the historical record that doesn’t add up.

Cholera is a bacterial infection that causes severe abdominal cramps, violent diarrhea and projectile vomiting that, if untreated, leads to death by dehydration. By the summer of 1832, a global epidemic of cholera had arrived on the East Coast of America and was killing about 80 people a day in the Philadelphia region during its peak in early August. Before it was over, the cholera outbreak would kill 900 in the Delaware Valley.

The infection soon spread to the workers at Duffy’s Cut and by late August, according to archival accounts, all 57 had succumbed. The men lived in a shanty of tents at the bottom of a deep, wooded valley located a stone’s throw from mile 59, and it was there that they would be buried in unmarked graves and covered over with the dark, loamy earth they had shoveled out of Duffy’s Cut just weeks prior. And it was there that they would remain, forlorn and forgotten, if not for the efforts of the Watson brothers—Bill, chairman of the history department at nearby Immaculata University, and Frank, a Lutheran pastor with a Ph.D. in historical theology—and a small volunteer army of archaeologists, forensics experts and history students.

And despite near-zero funding, the skepticism of many and the outright obstruction of others—the Watson brothers’ team has dug for eight years through a historical paper trail and the tick-infested valley at Duffy’s Cut searching for the remains of the men and the truth about what happened to them.

When the 57 Irishmen disembarked at Philadelphia, they were intercepted by Phillip Duffy, a subcontractor tasked by the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad with laying several miles of track near present-day Malvern. The new rail line Duffy was helping to build would connect Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, reducing what was in those days a two-to-three week trek to a mere two-to-three days, and in the process create the Main Line.

Duffy, himself an off-the-boat Irishman, likely spoke fluent Gaelic, with which he was quickly able to secure the labor services of the new arrivals from Derry. The men would be paid 25 cents a day and all the whiskey they could drink to lay mile 59. The work was hard, dirty and back-breaking, something the men had invariably grown accustomed to back in Ireland, where most people worked themselves to the bone in exchange for the right to grow potatoes on a small plot of land.

“The railroads must have been thinking, ‘We have to get the Irish, they are the only ones who would tolerate that kind of work,’” says Bill Watson. “Southern plantation owners wouldn’t even rent their slaves out for railroad digging, it was just too harsh.”

A dark shadow looms over the valley at Duffy’s Cut, dubbed Dead Horse Hollow because the carcasses of dead horses were allegedly dumped there back in the day. Some say it’s cursed, other say it’s haunted. But for the 178 years since the 57 Irishmen died there, the valley has remained untouched by development or, for that matter, any manifestation of modernity.

“Bad stuff happened there and you feel that the longer you are there,” says Frank Watson. “I’ve been down there a couple of times by myself and it creeped me out. When this all started, none of us wanted to be there by ourselves.”

Today, a housing development stands at the top of the valley, and former residents have told the Watson brothers about the strange, unexplained phenomenon they witnessed when they lived there. Two separate teams of ghost busters have gathered evidence of paranormal activity at Duffy’s Cut—photographs that captured eerie phosphorescent orbs and recording devices that picked up disembodied voices with startling clarity. One such recording reportedly captured a voice saying “Help me.”

In fact, the ghost stories surrounding Duffy’s Cut stretch all the way back to September of 1832, just weeks after the 57 died. An unidentified man walking home after dark from the nearby Green Tree tavern took a shortcut along the railroad tracks. He describes the night as “hot and foggy,” according to an account found in the Pennsylvania Railroad’s files, and when he got to the section of track by Duffy’s Cut he claims he saw the ghosts of dead Irishmen dancing on their mass grave. “They looked as if they were a kind of green and blue fire, and there they were hopping and bobbing on their graves,” he said.

In fact, the ghost stories surrounding Duffy’s Cut stretch all the way back to September of 1832, just weeks after the 57 died. An unidentified man walking home after dark from the nearby Green Tree tavern took a shortcut along the railroad tracks. He describes the night as “hot and foggy,” according to an account found in the Pennsylvania Railroad’s files, and when he got to the section of track by Duffy’s Cut he claims he saw the ghosts of dead Irishmen dancing on their mass grave. “They looked as if they were a kind of green and blue fire, and there they were hopping and bobbing on their graves,” he said.

Fast forward to the night of Sept. 19, 2000. Bill Watson and friend Tom Conner were returning from a bagpiping performance for World War II veterans out in Lancaster, still wearing the full-on Celtic regalia—kilt, tunic, and dirks—they don for such events. They stopped in at Bill’s office at Immaculata University to use the bathroom and get some coffee from the vending machine. They used the men’s room on the first floor of the faculty office building. Conner looked out the open window and saw something he couldn’t quite grasp.

“What am I looking at?” he said to Bill, who then took a look for himself. What he saw stopped him in his tracks: three figures with tiny heads standing side by side, their legs opened in a V formation and their arms stretched out to their sides. The figures glowed on the darkened lawn as if made of neon. The men were not spooked by what they saw until the three illuminated figures abruptly disappeared. They ran out of the bathroom but when they finally got up the nerve to go outside and investigate they found nothing.

“I believe in the supernatural,” says Bill Watson. “Do I believe in ghosts, like Casper the Ghost? I don’t know. I just know that there’s a lot of strange coincidences that have piled up over the years.”

Eventually, Bill Watson’s memory of the incident faded—until Labor Day 2002, when he was hanging out at his brother’s house. Both Watson brothers have been fascinated by railroad lore since childhood, an interest stoked by their grandfather, an executive with the Pennsylvania Railroad who imbued both men with an abiding curiosity about history, specifically the history of the railroads and the central role they played in bringing the country into modernity. After his death, the Watson brothers inherited his vast collection of history books and various ephemera and artifacts from his days at the Pennsylvania Railroad. Amongst these materials was a file about the tragedy at Duffy’s Cut that had been kept under lock and key by railroad executives all these years. Bill Watson picked up the file and began paging through it. When he got to the ghost story about the glowing Irishmen “hopping and bobbing on their graves,” he stopped dead.